-

Homepage

-

Blog

-

We Take an Economics Exam on Relating Investment to Other Decisions

Fall 2022 Final Exam Solution on Relating Investment to Other Decisions at the Duke University

The following blog answers an economics question relating investment to other decisions in the fall 2022 final exam at Duke University. Our relentless

economics exam solvers are available to

take your macroeconomics exam for all levels, including topics relating investment to other decisions. If you need help with your statistics exam, you can contact us or submit your order details.

Exam Question: what models are used in managerial economics to relate investment to other decisions?

Exam Solution: Managerial economics is continually evolving, and one of the most interesting recent developments has been the production of a theory of how firms could structure their long-term ('investment-like) decision-making around the concept of discretionary cash flow. This approach sees the outlays of the firm as being divided between those which are contractual, such as wages, rent and materials costs, and those which can be postponed, such as dividends, marketing expenditure, research and development and investment. Thus at any one time, all the firm's cash flows can be divided into 'non-discretionary' (contractual) or 'discretionary' (postponable). The innovation is to perceive that the discretionary expenditures are thus competitive and that some criterion for deciding between them is necessary. This chapter deals with the model developed to deal with this perception and how using it might change firms' behaviour.

Origins of the Model

We can trace the origins of the discretionary fund's flow maximization model to its four separate components. These are the neoclassical theory of the firm's idea that firms attempt to maximize profit, the work of accountants (and some economists) on 'flows of funds' within the firm, the work of econometricians on how firms allocated funds and the corporate models of the 1960s which often centred on the income statement of the firm. We shall discuss each of these in turn and then outline the model.

Neoclassical theory of the firm

The neo-classical theory had shown that the assumption of a maximizing firm had produced a coherent account of what firms would do and that maximizing firms could be more consistent in their decision-making and thus more cohesive units. After the disappointments with behavioural and managerial theories (see Chapter 7), which used either satisficing or joint maximization of several objectives, maximizing one objective became appealing again.

Funds flow analysis

One of the intellectual growth areas in accounting in the 1960s and 1970s was analyzing the 'flows of funds to, from, and within firms. Firms began to produce flows of funds statements in their annual accounts, and research was funded in the universities, such as that reported by Bain, Day and Wearing (1975).

Corporate models

Many of the corporate models of the 1960s had, as we saw in Chapter 9, been 'planning-structure' models organized around the annual income statement of the firm. Thus they drew attention to the sources and uses of funds and indirectly emphasized that the allocation of funds was discretionary. In addition, the clear distinction in these models amongst environmental, control and performance variables invited research on the exact effect of different control variables on the performance targets. No doubt, the firms carried out and sponsored research. We now look at examples of research not directly funded by firms.

Econometric research

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw a great deal of research on econometric models of firm behaviour, i.e. models of firms with reasonably clear statistical evidence for the cause-and-effect relationships included in the model. Most models only considered an aspect of particular interest, such as advertising or research and development. Still, we can outline three which did cover a number of the firm's major decisions. They are by Salzman (1967), Mueller (1967) and Elliott (1972a).

Salzman This model represented a single, anonymous subsidiary of a large US corporation. The data covered 36 quarters, and the model had 10 equations with 10 environmental variables, 8 control variables and 8 performance variables. The most interesting results showed the effect of changes in sales and profits on the control variables, i.e. how the firm changed its decisions in response to changes in sales and profits. The results were expressed as elasticities, i.e. % change in the control variable divided by % change in sales (or profits). Elasticities greater than one was found for marketing expenditures, investment and 'manufacturing engineering expense' in response to changes in sales. Elasticities between 0 and 1 were found for research and development and administrative expense in response to changes in sales revenue. Changes in profits harmed marketing expenditures, investment and 'manufacturing engineering expense'. Thus we have evidence for one part of the theory, which was to develop how firms allocate their discretionary funds to competing uses such as marketing expenses, research and development and investment.

Mueller This model uses annual data for 67 firms from 1957 to 1960. It was assumed that the ob- objective of each firm was to maximize the present net worth of the shareholders, which is to maximize the present value of their equity in the company. Thus the idea of discounting future earnings was explicitly recognized. (See Chapter 17 to explain the present value and discounting.)

Mueller assumed that the firm would allocate its funds first to necessary production expenses such as materials, wages, etc., then to contractual payments such as overheads and preference dividends and interest on borrowed money and that what was left could be termed the 'discretionary funds flow. This flow could then be allocated amongst four competing uses: dividends for 'ordinary' shares, advertising, R and D and investment, and the allocation to each would be affected by three factors. First is the effect of advertising, research and development and investment on the firm's future cash flows. Second, the effect of each of the four expenditures on share values (which, of course, directly affects the net worth of the shareholders), and lastly, the time preference of the shareholders, which of course, decides the rate at which future cash flows should be discounted (see Chapter 17).

Mueller found that the variables which best 'explained' the actual decisions made on allocating 'discretionary funds' fell into four categories. First were the 'enabling' variables, sales and profits; then, there was the effect of past decisions to spend money for this purpose. Thirdly some expenditures were 'imitative' of what was happening in the rest of the industry. Lastly, there was some 'competition' from the other discretionary expenditures.

Many detailed results duplicated those found by other studies and observations; for instance, advertising was not treated as competitive with other use of funds but rather more as a 'necessary expense'. R and D and advertising seemed to be very 'imitative', dividends were not very competitive with investment, and R and D were a stimulus to future investment. Overall the finding seemed that the 'discretionary' uses of funds were subject to considerable discretion.

Elliott Elliott has produced several studies of the discretionary cash flow process (Elliott, 1971a, 1971b, 1972a and 1972b), and we refer here to the most general model (1972a). Essentially the model marries the income statement approach of corporate models with Meuller's econometrics. The result is a model much larger than Mueller's but statistically probably less reliable, as shown in Table 20.1. The number of observations is less spread over a very long period when numerous factors not included in the data must have changed considerably. The results, however, are very interesting, showing the influence of discretionary cash flow on marketing, R and D and investment expenditures, the importance of previous activity levels, and specific environmental variables such as the money supply. Elliott has outlined what amounts to a new theory of the firm (Elliott, 1973). What follows owes a great deal to Elliott but differs in several respects; for details, see the further reading.

Table 20.1. Discretionary cash flow models:

| Mueller | Elliott |

Number of equations |

4 |

11 |

Environmental variables |

3 |

6 |

Control variables |

6 |

16 |

Performance variables |

4 |

6 |

Number of observations |

268 |

189 |

|

(4yrs x 67 firms) | (21yrs x 9 firms) |

The Discretionary Funds Flow Model

The model essentially has two aspects, positive and normative. The positive aspect is based on the research and asserts that it is possible to predict how firms will allocate their discretionary funds. The Normative aspect deals with maximizing the discretionary funds flow to increase the shareholders' net worth. It is not suggested that firms try to maximize their dis- accretionary cash flow, only that they would be worth more to their owners if they did! If we look at the 'positive' aspect of the first, we can see that it breaks down into five questions which can be answered in turn.

What are discretionary funds?

Discretionary funds are most easily identified using Table 20.2, where we define 'internal discretionary funds flow', and in this theory account, we shall not consider external flows other than in passing. Objectively, the firm should realize that the five uses of discretionary funds are competitive.

Table 20.2. Discretionary cash flow: definition Mueller and Elliott

How competitive are discretionary flows?

The extent to which the firms compete depends on the following:

- The size of the discretionary income

- The perceived 'productivity' of each alternative

- The perception that they are competitive.

In easy market conditions, firms often have relatively large amounts of discretionary funds and little apparent incentive to engage in R and D and marketing expenditures. Thus there is little objection to high ordinary dividends and investments. Worsening conditions will lead to pressure for more marketing expenditure and would justify more R and D to safeguard the future. This simple scenario may explain why many firms neglect R and D in good and bad market conditions! Finally, we can note that some discretionary expenditures may be protected from 'competition' because they are felt to be "necessary'. In Mueller's (1967) study, firms often treated marketing expenses as a priority and were not seen as under pressure when discretionary funds were squeezed. Whether this occurs will vary from firm to firm and most probably according to the background of individual managers.

Is discretionary income predictable?

We can answer this question by looking at previous econometric investigations or, logically, at the definition in Table 20.2. The investigations give us hope that it can be found in practice, and the model appears straightforward. If we assume that firms have some expertise in prediction, they will have an estimate of future sales and non-discretionary expenses.

An analysis of the firm's income statement (such as that in the Xerox model in Chapter 9) will show the influence of environmental and control variables on the different items and provide the structure of an estimating model.

Are discretionary expenditures predictable?

The econometric work of Mueller (1967) and Elliott (1971a and b, 1972a and b) have shown the possibility of predicting the response of firms to changes in their discretionary cash flow. As in macroeconomic models (Chapter 10), we can think of the firm as having a 'propensity to spend money on investment/R and D/marketing/ dividends. It is also possible to produce funds flow multipliers which link changes in exogenous variables (such as GNP/industry sales/wage levels) to changes in discretionary expenditures.

What feedbacks exist?

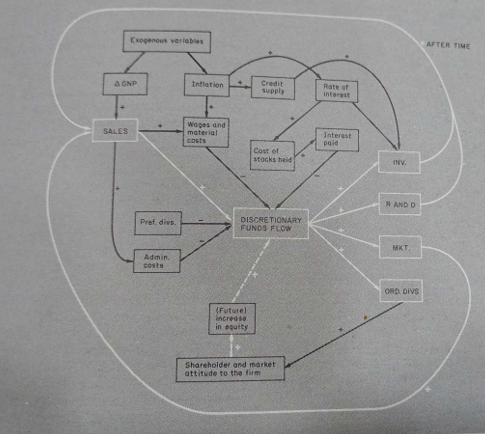

We also need to know how the discretionary expenditures will react (feedback) to the discretionary cash flow. We have a simple example in Figure 20.1 showing them acting through effects on sales or total revenue. The signs (+/-) show the effects which are expected. For example, increases in sales will increase discretionary expenditures. Higher ordinary share dividends will improve shareholder and stock market attitudes toward the firm and thus make future calls for equity easier. Marketing expenditure will tend to increase sales, R and D and investment, although these will take more time than marketing to achieve this. Thus, we now have a model in which, in principle, we can use data on a firm's past behavior to determine the parameters for each of the relationships shown in the diagram. Once we have estimated the parameters, we could investigate the stability and dynamics of our model and the particular firm in question. (See Chapter 10 for an explanation of stability and dynamics.)

Fig. 20 1 Discretionary funds flow: a simple model

The Normative Model

Having seen how we might model actual firms' decisions on allocating their discretionary funds, we now suggest how firms could improve their performance.

We start by assuming that the objective is to maximize the net worth of the shareholders. We then need a measure of shareholders' equity in the company. This could be provided by the stock market's current value of the shares. This is related to the prospects of the firm as perceived by current and potential investors. The prospects have two aspects, dividends and capital appreciation. Both are effectively decided (as far as the firm can decide them) by the discretionary funds flow and how it is used: thus, the larger the discretionary funds flow, over time, the larger the net worth of the shareholders.

If the previous (telescoped) argument has been followed, it is easy to see where it leads. The net worth of the shareholders will be maximized when the discretionary cash flow is maximized. If the firm plans its discretionary expenditures to create as much future discretionary cash flow as possible, shareholders can decide how to use the discretionary funds. Using them for dividends reduces future sales but increases their present equity. If they use them for marketing, they increase discretionary flow shortly; if they are for investment or R and D, they safeguard future sales and thus discretionary income. Thus we return to the need to know the 'productiveness' of each discretionary expenditure on future discretionary cash flow and the time- preference of the shareholders, which gives the discounting applied to future flows.