-

Homepage

-

Blog

-

Determine Who Takes Decisions on Marginalist Theories Exam

2022 Semester Exam Solution on Marginalist Theories from the Northwestern University

This information features an economic-related question for the 2022 semester Exam Solution examined at northwestern university. Solutions to this question have been explained well, and major points stand out. This read allows everyone to learn about what major contributors say concerning marginalist theories. Moreover, we are a click away if you want to hire us to

take your economics exam. Our experienced

microeconomics exam takers will be glad to offer the needed help.

Exam Question: explain major marginalist theories and how their contributors distinctively argued

Exam Solution: One of the crucial assumptions of the marginalist theory of the firm, and indeed almost all other theories, is that decisions are taken in a unitary manner. Early theories assumed what was then very common, the owner-manager or sole proprietor. He identified the business's profit with his income and thus tried to maximize profits. However, the advent of a large company with thousands of shareholders meant that owners could not be managers. Some theories explore how these managers might make different decisions from owner-managers and why. As a group, they are called managerial theories. We then look at theories which concentrate on the complexity of decision-making in a large company and how this is organized, usually termed behavioural theories. Finally, we discuss the value of these theories of the firm.

The Managerial Revolution

Since the work of Berle and Means (1932), attention has been directed to the separation of ownership and control in large companies. Such companies commonly have thousands of shareholders who obviously cannot all participate in decision-making and managers who do not usually have large shareholdings, if they have any. Thus the shareholders can be expected to have the traditional interest in profit, while the managers will view the business more as employees. If we examine Berle and Means's ideas more closely, we see that they are putting forward four hypotheses which can be compared with the available evidence:

- That economic power is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few large manufacturing companies;

- That their assets are controlled by professional managers who do not own large proportions of their shares;

- That they do not have to raise much money from the capital market and thus do not have to be profit-orientated; and

- That managers tend to develop a 'corporate conscience' which leads them away from the less acceptable aspects of profit maximization.

We now look at the evidence for each hypothesis.

The concentration of economic power

We can find evidence that economic power is concentrated and agree that this power is growing, as Berle and Means (1967) show % of Net Capital Assets of US manufacturing companies owned by the 100 largest companies

1929 44

1962 58.4

However, this still leaves a sizeable proportion of manufacturing output coming from the smaller firms and does not tell us anything about the much larger 'service' sector of the US economy.

Separation of ownership and control

Evidence for this hypothesis is conflicting. In the UK, the percentage of a firm's shares held by its directors appears to have declined - from 2.8% in 1936 to 1.5% in 1951 (Florence, 1961). The average value of directors' shareholding remained low:

1936 £25,000

1951 £21,000

1955 £28,000

However, in the US, Lewellen (1971) has shown that the top managers in large companies do hold considerable blocks of shares:

Average holdings of the four top managers after the chief executive

1953 $ 300,000

1963 $2,300,000

Thus managers of US companies might be expected to be more concerned with profits and dividends than UK managers. Still, we do not have any strong evidence to support this logical deduction. The other aspect of the separation of ownership and control is that managers are not vulnerable to shareholder pressure because shareholdings are so fragmented. There is an interesting discussion of this point in the further reading by Wildsmith. Here we can mention the evidence that shareholders attack the directors of companies that perform badly and that many companies now have large, 'controlling blocks of shares held by financial institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies, which are very interested in profits. Thus the idea of the 'irresponsible' management of large companies seems less credible than if we merely list the actual number of shareholders in a large company.

Insulation from market pressure

Berle and Means suggested that large firms tended to obtain about 60% of their finance from profit, about 20% from loans, and only 20% from the capital market by issues of shares, thus effectively minimizing the influence of investors on their performance. If they did not need to raise much money from the market, they did not need to pay as much attention to profitability and dividends. Again there is an interesting discussion of the evidence in Wildsmith's book. We can add that managers will become more profit conscious as they become more 'professional' and apply discounting techniques to investment decisions. Having internally-generated funds may not make them less profit conscious because the internal funds are dependent on creating profit, and 'professional' analysis of investment opportunities tends to disregard the source of funds and concentrate on its most profitable use. (This is explained further in Chapter 17.) Thus the insulation from market pressure is perhaps less than, and less important than, Berle and Means suggested.

During the 1960s, there appeared another limitation on the freedom of managers to disregard profit. This was the rise of individuals and firms which specialized in 'taking over' other firms. Individual cases are often complex, but the basic principles of takeovers are very simple. A firm is worth taking over if the present management is not producing as high a return from its assets as it is reasonable to expect. Thus firms which do not pay much attention to profit will be vulnerable to bids for their shares, and a large number of shareholders will then be a disadvantage to the present management. So managers may be wary of letting the market valuation of their company slip too much by not paying adequate dividends.

Corporate responsibility

The idea of business having responsibilities beyond its owners or shareholders is not new, but economists have often been very sceptical of businesses- men's good intentions towards others. Adam Smith was noted for his distrust of business people's motives and stressed that the good results of capitalism came because they followed their self-interest rather than because of their goodwill to others. However, it is now common to see statements, such as the following, about how the managers of Exxon conduct its affairs in such a way as to maintain an equitable and working balance among the claims of the variously directly interested groups - stockholders, employees, customers and the public.

Quoted by Mason (1958)

It is difficult to decide just how far interests are coincidental, and helping others helps to make a profit, how far they are neutral and effectively costless to the firm, and how far they involve public relations. Any action beyond this point involves sacrificing the shareholders' interests for those of another group and thus may eventually lead to shareholder resistance. However, shareholders sometimes press companies to take actions that appear to hurt profits. The shareholders of Distillers, the UK manufacturers of Thalidomide, urged the company to increase its voluntary compensation to the drug's victims. Some shareholders have urged the disposal of shares in firms making arms or selling to politically unacceptable regimes.

A standard reaction by economists has been that firms are not qualified to make moral judgements of the kind implied in the statement above attributed to Exxon. However, whether managers ought to use shareholders' money this way is irrelevant here: whether they do. If they do, we may need to incorporate this into any 'managerial' theory of how firms behave.

Managerial Theories

Marris

In 1964 Marris produced a model in which the managers' main objective was to maximize the firm's size. He assumed this was to demonstrate competence to their peers and superiors and achieve power, status and higher material rewards. In the model, profitability was seen as a constraint on growth. Profits have to be satisfactory so that investors will keep the share value high and thus discourage takeover bids from other firms. Some implications of 'growth- maximization' are explored in the further reading by Crew.

Williamson

O. E. Williamson (not to be confused with J. H. Williamson, who clarified Sales Revenue Maximization models of the type covered in Chapter 5) produced the best-developed managerial theory. It assumes that managers have a utility function they wish to maximize, containing three variables that must be traded against each other. They are:

- Staff, the more subordinates the manager has, the greater his feelings of security, status, power, prestige, and likelihood of esteem by professional colleagues.

- Emoluments - managers are particularly concerned about 'perquisites', above a normal salary for their job.

- Discretionary profits - managers like to make slightly more profit in their area than is strictly necessary or budgeted.

Some of the results of having a 'utility function' such as this are also explored in further reading by Crew.

Achievements and failures

The main achievement of managerial theories is that they attribute plausible motives to managers and incorporate these objectives into a coherent model. Wildsmith (1973) argues that managerial theories, in some sense, culminate the firm's theory, giving it a dynamic aspect that marginalism lacked. Thus a dynamic (growth-orientated) firm's actions would best be explained by a managerial theory, while static conditions might be left to traditional marginalism.

Behavioural Theories

Managerial theories allow for the separation of ownership and control; some theories go further and allow for differences of interest within a firm's management. To do this, they must represent the firm as a complex organism responding to outside stimuli. Because there are obvious analogies with the behaviour of biological phenomena, these theories are usually called behavioural theories.

Forrester

Although he is not the best-known of the behavioural theorists, Forrester (1961) has probably explained most clearly what the approach entails. He says that there are four 'cornerstones' to his models:

- 'the theory of information feedback characteristics how stimulus and response can be modelled:

- knowledge of the decision-making systems used by the firms being modelled;

- simulating the behaviour of the firm over time rather than producing an analytical optimizing model;

- and using computers to run the simulation models produced.

In the early sixties, there was considerable optimism about computer simulation, partly at least because it opened the door to more complex simulation models. Economics has always had some simulation or iterative models, such as duopoly (in Chapter 8 of this book) or the cobweb model we met in Chapter 2. Still, computers meant they could be more ambitious. Forrester, and some enthusiasts, went further:

Mathematical analysis is not powerful enough to yield general analytical solutions to complex situations encountered in business. The alternative is the experimental [simulation] approach.

Forrester (1961)

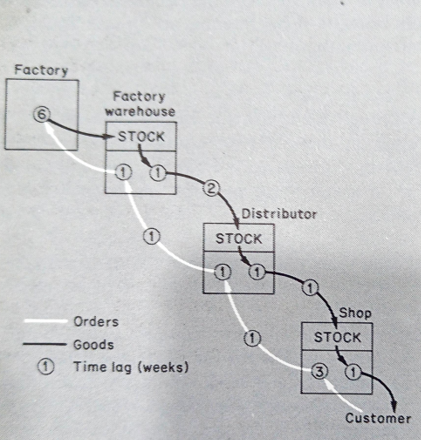

An example of a situation where Forrester appears to be correct is when we try to predict the effect of changes in orders on the stock levels of different firms in an industry. Figure 7.1 outlines the system that we are modelling. The customer orders 10% more than in the past, and we follow the effects through the system. We assume, for simplicity, that the lags are known with certainty. No orders ever get lost in the post or are misinterpreted! The lags are of four kinds: (i) perceiving a shortage and making a decision; (ii) transmitting the order;

Fig. 7.1 Lags in ordering and supplying

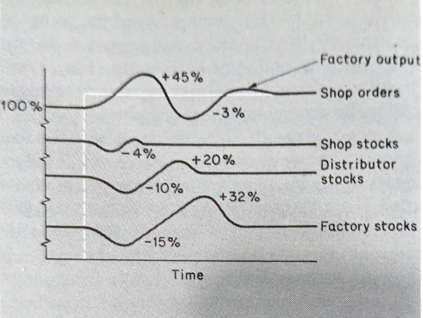

Fig. 7.2 Graphs of lags in a supply chain

- changing production or dispatching plans; and

- Transport time. The effect of the lags produces late and exaggerated responses to the customers' change in demand, as shown in Figure 7.2.

Thus Forrester argues that simulation is often the only way to model complex business situations. In this, he unconsciously echoes the feelings of many economists dissatisfied with simple analytical theories. The classical economists often argued (as in the Cournot model in Chapter 8) that more firms meant more competition. At the same time, neoclassical models also postulated a relationship between an 'industry' structure and firms' behaviour. Triffin (1940) was one of the economists who argued most strongly that it was impossible to determine what firms would do from an industry's structure. For him, each firm had to be examined individually to determine how it would behave. Forrester is saying the same, and for him, there is no 'theory of the firm' but rather a model which can be built for each firm. (We return to this theme in Chapter 9, where we consider the models firms build for their use.)

Cohen, Cyert, March and Simon

The best-known behavioural theories are associated with the above group of authors. We examine the best-known version of their approach, as contained in Cyert and March's (1963) book.

The basic model is, like Forrester's, deterministic and dynamic. It sees the firm as a coalition of different departments and central management. The departments perhaps function as production, transport, marketing and purchasing, or different selling units such as in a department store. Are where performance is monitored, controlled and achieved. They have a great say in setting their aspirations or budgets and bargain with the central management and other departments. The central management runs the mechanisms which ensure that:

- The firm's goals are adjusted and reviewed:

- Crucial problems are identified;

- Departments' needs and demands are reconciled: and

- The structure and organization are changed when necessary.

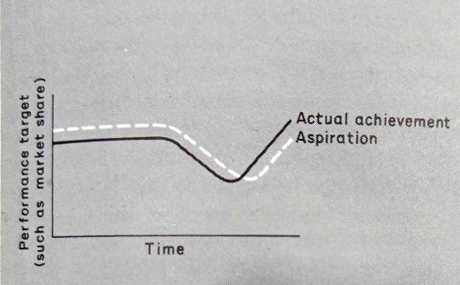

Fig. 7.3 Behavioural theory: adjustment of aspirations

The 'behavioural' firm carries out several distinctive activities. One is adjusting its 'aspirations' to what can be achieved, as shown in Figure 7.3. Generally, they appear to lag behind the performance, so the firm will consistently underachieve its aspiration when performance falls. When performance improves, it will tend to run ahead of aspiration or budgeted targets. If performance stabilizes, aspiration will tend to be higher than present performance.

Another crucial innovation in the theory is the assumption that some of the firm's goals will be satisfied. The firm will be content with a 'satisfactory' performance rather than the best. This is a similar approach to the 'sales revenue maximizing subject to a satisfactory rate of profit' model, which we met in Chapter 5, but different from the managerial utility function of Williamson, which involved maximizing each variable so long as it did not reduce another objective. The behavioural firm 'does not bother about some of its objectives once a satisfactory performance is achieved. It concentrates on unsatisfactory performance and rewards overachieving departments with organizational slack. This reward, allowing a rather easier time to those who achieve, is called a side payment and is often in the form of 'perks' or 'emoluments', as Williamson called them. So, in summary, the behavioural firm adjusts its aspirations dynamically and satisfies them rather than maximizes them.

Achievements

The achievements of behavioural theories were clearly stated in the early 1960s by Clarkson and Simon (1960) and Cohen and Cyert (1961). They fall into three categories:

- The incorporation of more detail and complexity into a model than had hitherto been possible;

- The incorporation of realistic assumptions about the behaviour of managers in different departments of a firm;

- Allowing models would not be possible if the model builder tried to obey the normal rules of mathematical model-building. Thus a behavioural model need not have the same number of equations as variables, and some of the statements in the model will not be equations but algorithms describing the behaviour of different departments if certain conditions exist.

Behavioural models are also truly dynamic because they involve heuristic processes (moving towards a solution, 'learning' to accept new aspirations, and changing emphasis on different goals over time).

Criticisms and failures

After the early enthusiasm of the pioneers, we have seen little published material on behavioural models of firms. Naylor and Vernon (1969) sum up the probable reasons very well;

- Adequate data is difficult to obtain, and confidentiality problems may have prevented economists from obtaining the cooperation of suitable firms.

- Firms which have constructed their models may have become reticent to reveal them to the public for competitive reasons. (We return to this problem in Chapter 9.)

- Behavioural models do not lie within the competence of any academic discipline, although economics and behavioural science are its main inputs. Thus inter-disciplinary teams are needed to create such models, and they are difficult to assemble outside industry and government.

We also know little about what would be suitable criteria for saying whether a particular model was good. This experimental design problem is considered by Naylor and Vernon, as cited in the further reading.

The last reason for the slow take-off of behavioural theories may be the resurgence of marginalism. Many economists agree with Machlup (1967) that marginalist models may be adequate for the situations they wish to investigate.

Thus managerial and behavioural theories provide us with detailed models of the process of decision-making by professional managers. In this respect, they appear to complement rather than compete with the simpler and more aggregated, maximizing theories of Chapter 5.